I. THE COMMISSION AND ITS DELIBERATIONS

II. FIDUCIARY APPOINTMENTS IN NEW YORK

A. Categories of Fiduciary Appointments

B. Regulation of the Fiduciary Appointment Process

C. The Administration of Part 36

III. CONCERNS WITH THE EXISTING PROCESS

C. Problems Identified by the Special Inspector General and the Auditors

D. Problems Identified by the Commission

IV. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

A. Eligibility and Qualifications

C. Oversight of the Appointment Process

APPENDIX

B. Individuals Who Met With the Commission

C. Individuals Testifying at Public Hearings

E. Commission's Interim Recommendations -- Oversight of Filing Process

F. Chief Administrative Judge's Memorandum -- Oversight of Filing Process

A. Eligibility and Qualifications:

Training Should be Required for Inclusion on the Fiduciary Lists.

State and County Political Party Leaders and Their Immediate Relatives and Law Firms Should be Ineligible for Appointment.

Immediate Relatives of Higher-Level Nonjudicial Employees Should be Ineligible for Appointment.

Former Judges Should be Ineligible for Appointment for Two Years After Leaving the Bench.

The Rules Should Clearly Provide that Criminal Offenders and Disbarred or Suspended Attorneys are Ineligible for Appointment.

Information Regarding a Fiduciary's Bankruptcy History Should Continue to be Available.

Procedures Should be Adopted to Remove Fiduciaries From the List for Good Cause.

B. The Appointment Process:

Judges Should Have Full Authority to Select the Fiduciary.

Judges Should Select Fiduciaries From the OCA List.

Specialized Fiduciary Lists Should be Created.

Re-registration Should be Required for All Those on the Fiduciary List.

Additional Types of Appointees Should be Governed by the Fiduciary Rules.

Additional Types of "Secondary" Appointees Should be Governed by the Rules.

New Limits Should be Imposed on the Number of Higher-Paying Appointments that Individual Fiduciaries may Receive.

Judges Must be More Scrupulous in Reviewing Applications for Compensation.

Limits Should be Imposed on Appointment of Other Article 81 Fiduciaries as the Guardian.

C. Oversight of the Appointment Process:

All Persons on the Fiduciary List Should be Assigned an Identifying Number.

Law Firms Should Report More than $25,000 in Fiduciary Compensation.

Compensation Should be Reported to OCA in All Cases, Even Those in Which No Compensation is Received.

Periodic Audits Should be Conducted of the Fiduciary Filing Process.

D. Additional Recommendations:

The Revised Fiduciary Rules Should Include a Preamble.

Judges Should Receive Training on the Fiduciary Appointment Process.

The Court System Should Designate an Ombudsman to Provide Information and Field Complaints About the Fiduciary Process.

Public Funds Should be Available to Compensate Article 81 Guardians in Cases Involving Minimal or No Assets.

Where Practical, Article 81 Cases Should be Assigned to a Small Group of Judges in Each Jurisdiction.

An Administrative Support Office Should be Created as a Resource for Judges Handling Guardianship Matters.

Attorneys Should not Contribute to Judges' Campaigns for the Purpose of Receiving Fiduciary Appointments.

"[P]ublic confidence in the courts is put at risk when judicial appointments are based on considerations other than merit. Simply put, the public must have faith that the courts operate free of favoritism and partiality."

Chief Judge Judith S. Kaye, State of the Judiciary address, January 10, 2000.

Fiduciary appointments are judicial assignments of individuals, usually private attorneys, to assist the courts and serve litigants in a variety of situations. For example, a court may appoint a receiver to manage a property that is the subject of litigation; a guardian to handle the affairs of an incapacitated person; or a guardian ad litem to represent the interests of a child or incapacitated person involved in a Surrogate's Court proceeding. Fiduciary appointees generally receive their fees from the assets of the individual or business the fiduciary has been assigned to represent or manage. Although in many cases the fees are relatively small or even non-existent, in some cases they can be quite lucrative.

Fiduciary appointments have long been a subject of public attention and controversy. Over 130 years ago, Benjamin Cardozo's father, Manhattan Supreme Court Justice Albert Cardozo, was harshly criticized and ultimately forced to leave the bench in large part because of his repeated appointment of relatives and political cronies as fiduciaries.1 Although public criticism of the process continued through the years, extensive regulatory limitations on appointments did not arise until the 1980s, with the promulgation of Part 36 of the Rules of the Chief Judge.

Even with the promulgation of Part 36, however, public concerns about the fiduciary appointment process have persisted. Indeed, these concerns may have reached their peak in January 2000, when a controversial letter written by two politically-connected Brooklyn attorneys who had received numerous fiduciary appointments was made public. In their letter, the attorneys complained that, contrary to what they perceived to be the "long-standing practice" in Brooklyn, certain lucrative fiduciary appointments were being assigned to another attorney who, although having close ties to a top political party official, had no record of party service and thus had not demonstrated his "entitlement" to the appointments. To many, the letter confirmed the widely-held perception of the inappropriate influence of politics on the fiduciary appointment process.

In response to these developments, Chief Judge Judith S. Kaye, in her 2000 State of the Judiciary address, announced a three-part program to reform the fiduciary appointment process. First, she created the Office of the Special Inspector General for Fiduciary Appointments, with authority to investigate violations of the fiduciary rules and recommend referrals of such violations to appropriate disciplinary and other enforcement authorities. Second, she directed the State's Administrative Judges to evaluate the fiduciary appointment process in their judicial districts and suggest operational changes that should be made. Finally, Chief Judge Kaye established the Commission on Fiduciary Appointments, with the responsibility to examine the existing rules and procedures governing fiduciary appointments and offer recommendations to improve them.

This Report is the result of over a year of painstaking analysis of New York's complex fiduciary appointment process. The Commission interviewed scores of judges, attorneys, court personnel and others familiar with the process; it examined reports, recommendations and related materials submitted by judicial associations, bar associations and other interested organizations; it conducted public hearings; it reviewed voluminous fiduciary appointment data; and it surveyed fiduciary appointment practices in other jurisdictions across the nation.

Based on this extensive study, the Commission found that many fiduciary appointees are fulfilling their obligations with considerable skill and professionalism -- indeed, the Commission was impressed to learn of the hundreds and hundreds of cases in which fiduciary appointees serve for minimal or no compensation. But the Commission also found extensive and significant flaws in the existing process. This Report presents the Commission's findings, and offers detailed recommendations for addressing these problems so that full public confidence in the integrity and impartiality of New York's fiduciary appointment process may be maintained.

In creating the Commission on Fiduciary Appointments, Chief Judge Kaye chose a broad cross-section of leaders of the bench, bar and academia. A list of the 17 Commission members and their backgrounds is attached as Appendix A. The Chief Judge's statement announcing the Commission noted that the Commission would "assess the effectiveness of the current regulatory structure" governing fiduciary appointments, and "evaluat[e] the efficacy of existing administrative rules." Among the issues that the Commission was charged with examining were "the appointment process, monetary limits on compensation, eligibility and expertise requirements for appointment and ethical standards pertaining to fiduciary assignments."

The Commission conducted an extensive, wide-ranging review of the fiduciary appointment process in New York, obtaining the views and recommendations of many individuals with day-to-day involvement and practical understanding of the process. For example, the Commission received presentations from and held briefing sessions with: the Presidents of the Supreme Court Justices Association of the State of New York, the Supreme Court Justices Association of the City of New York and the Surrogates Association of the State of New York, as well as individual judges with experience in this area; the Presidents, selected committee chairs and other representatives of the New York State Bar Association, the Association of the Bar of the City of New York and the New York County Lawyers Association; and the Chief Clerks of several Supreme Courts and Surrogate's Courts. The Commission also met on a number of occasions with Sherrill Spatz, the Unified Court System's Special Inspector General for Fiduciary Appointments. A complete list of the individuals who met with the Commission is attached as Appendix B.

In addition, the Commission conducted two public hearings: in Buffalo on November 29, 2000, at which judges and attorneys testified; and in Manhattan on December 7, 2000, at which judges, attorneys, litigants and other interested individuals testified. A complete list of persons testifying at the two public hearings is attached as Appendix C.

Commission members also held informational sessions with Supreme Court Justices and Surrogates during the two-week Annual Judicial Seminars in Rye Brook in July 2000, and they attended meetings of the State Bar Association's House of Delegates (July 2000) and Judicial Section (May 2000).

The Commission received numerous reports, recommendations and other written materials from various individuals and organizations, including the New York County Lawyers Association and committees of the State Bar Association and the Association of the Bar of the City of New York. The Commission also received and closely reviewed extensive information on fiduciary appointments collected by the Office of the Special Inspector General for Fiduciary Appointments and the Office of Court Administration's Internal Audit staff, as well as information from OCA's fiduciary database. Finally, the Commission examined fiduciary appointment practices in other jurisdictions around the country, and spoke with officials in those jurisdictions about their practices.

Early on, the Commission sought to identify the primary issues requiring examination. It then grouped the issues into three general categories -- (1) Eligibility/Qualifications for Appointment, (2) Appointment Process and (3) Oversight of the Appointment Process -- and established subcommittees for each of these categories. In the ensuing months, the subcommittees worked to develop proposed solutions for the problems, and it was those proposals that formed the basis for discussing and developing the series of recommendations the Commission offers in this Report.

A. Categories of Fiduciary Appointments

In New York, judges are frequently called upon to appoint fiduciaries to assist the court and provide services to litigants and other individuals. The primary categories of fiduciary appointments are referees, receivers, Article 81 fiduciaries (court evaluators, guardians, attorneys for alleged incapacitated persons and court examiners) and guardians ad litem.

Referees

Under New York law, courts have broad powers to delegate authority to referees to determine issues and perform functions on behalf of the courts.2 A primary purpose for which courts use referees is to sell real property that has been the subject of a judgment of foreclosure.3 Typically, the referee is appointed to compute the value of the property, and then sell it at a public auction usually held at the courthouse. The fees for these services are relatively small -- $50 to compute the value of the property, and $500 to sell the property (unless the property is of high value and the court authorizes a greater fee).4

Receivers

When there is a risk that property that is the subject of litigation may be "removed from the state, or lost, materially injured or destroyed," a person with interest in the property may move for appointment of a receiver to manage the property while the action is pending.5 The receiver is authorized to take and hold real and personal property and to sue for, collect and sell debts or claims.6 In the most common case in which a receiver is appointed -- a mortgage foreclosure proceeding -- this means that the receiver may collect rent and institute or defend lawsuits relating to the collection of rent or the eviction of tenants. The receiver's fee, which is paid from the proceeds of the property in receivership, may not exceed five percent of the total sums the receiver collects and disburses.7

Article 81 Fiduciaries

Under Article 81 of the Mental Hygiene Law, a court may appoint a guardian to provide for the personal care of an incapacitated person and/or manage the property and financial affairs of that person.8 When a petition for appointment of a guardian is filed, the court first appoints a court evaluator. The court evaluator conducts an investigation and submits a report and recommendations to the court addressing whether the alleged incapacitated person ("AIP") is in fact incapacitated, the availability and reliability of alternative resources and the selection of and powers that should be assigned to the guardian. In practice, the court evaluator is usually a private attorney, but he or she may be a physician, psychologist, accountant, social worker, nurse or any other qualified person.9 If the AIP is a patient in a facility such as a hospital or nursing home, the facility may be appointed as the court evaluator; or if the AIP has minimal or no assets, the Mental Hygiene Legal Service may be appointed.10

The AIP has the right to be represented in the proceeding by counsel of his or her choice. But in other situations, such as when the AIP requests counsel or the court determines that appointment of counsel would be helpful, the court may appoint counsel for the AIP.11

If the court determines, after a hearing, that the AIP is incapacitated and that appointment of a guardian is necessary, the court may proceed to appoint a guardian.12 In appointing a guardian, preference is usually given to a person nominated by the incapacitated person or to a family member.13 If the incapacitated person does not nominate anyone, and if no family member is available for appointment, the court must appoint some other "suitable" individual, usually a private attorney. In cases in which the incapacitated person has minimal or no assets, the court may appoint an appropriate social services agency or not- for-profit organization to serve as guardian.14

Along with providing for the personal care and/or managing the property and financial affairs of the incapacitated person, the guardian must file periodic reports and financial accountings with the court. The reports, which must address the incapacitated person's condition and care, and the accountings15 are reviewed by a court examiner appointed by the court. The court examiner, also usually a private attorney, submits his or her own report to the court evaluating the report submitted by the guardian.16

All persons appointed as court evaluators, guardians or court examiners must complete a training program approved by the Chief Administrator of the Courts.17 Article 81 fiduciaries generally are paid from the assets of the incapacitated person. Court evaluators and attorneys for AIPs are usually paid hourly fees based on the fair and reasonable value of their services.18 The court must establish a plan for the guardian's compensation, which may be based on a percentage of the amounts the guardian receives and disburses, a percentage of the incapacitated person's assets, an hourly fee or a combination of these or other methods.19 Court examiners are paid a set fee that is based on the amount of the incapacitated person's assets (the fees are set by the Appellate Division).

Guardians Ad Litem

Surrogate's Courts frequently appoint guardians ad litem to protect the interests of individuals incapable of protecting themselves.20 Under section 403 of the Surrogate's Court Procedure Act, appointment of a guardian ad litem generally arises when an unrepresented person under a disability is a necessary party to a proceeding and is incapable of adequately protecting his or her rights.21 Persons under a disability include infants, incompetent and incapacitated individuals, prisoners, unknowns and unborns.

The guardian ad litem, who must be an attorney,22 undertakes an investigation of the facts and reviews all operative documents (the will, trust, accounting, tax return, etc.) and other materials to determine if there has been compliance with applicable laws and procedures. Upon completion of the investigation and review, the guardian ad litem files a report with the court recommending whether objections should be made or other proceedings should be conducted to protect the interests of the ward.

The guardian ad litem's fee is generally paid out of the estate.23 The fee must be reasonable, based on the nature and extent of the services, the time spent, the stature and experience of the lawyer, the complexity of the issues and the results achieved.24

Secondary Appointments

In cases in which fiduciaries are appointed, "secondary" fiduciaries may also be appointed or retained to perform various services. For example, receivers frequently retain counsel and property managers to assist them with legal matters and day-to-day management of the property under receivership; guardians often retain counsel and accountants and other financial professionals; and guardians ad litem occasionally retain other professionals as "assistants" to help with their responsibilities. In some cases, secondary appointees can receive lucrative fees; in receivership cases, for example, the counsel's compensation (which is calculated on an hourly fee basis) often can exceed the receiver's compensation.

B. Regulation of the Fiduciary Appointment Process

Over the past several decades, a number of legislative and administrative efforts have been taken to promote fairness and openness in the fiduciary appointment process.

Judiciary Law § 35-a

In 1967, the Legislature enacted section 35-a of the Judiciary Law to "bolster confidence in the disposition of court appointments" by ensuring that information about the compensation of court appointees is made available to the public.25 Section 35-a originally required that all court appointees, other than those compensated with public funds, file with the Office of Court Administration a notice of appointment when appointed and a statement of award of compensation when paid.26 Several years of experience with this requirement, however, demonstrated that in a great many cases the appointees were not making these filings. Accordingly, in 1975, the Legislature amended section 35-a to eliminate the appointee's filing requirements and substituted the requirement of a single filing -- of the compensation awarded -- to be made by the judge, not the appointee.27 Placement of the filing requirement with the judge was considered a more reliable means of ensuring that the filings would be made.

Appellate Division, First Department Rules

In the 1970s, extensive public criticism of the fiduciary appointment process arose in response to the practice of certain Supreme Court judges in New York City to appoint close relatives of other Supreme Court judges. To address this problem, the Appellate Division, First Department, promulgated rules in 1977 for the Supreme Court in New York and Bronx counties (22 NYCRR § 660.24). Under these rules, the judge presiding over a case in which a fiduciary was to be appointed did not select the fiduciary. Rather, another judge of the court, whose name came up next on a strict rotational list, made the selection.

Silverman Committee Report

In 1978, shortly after its promulgation of section 660.24, the First Department also appointed a committee to study the fiduciary appointment process and make recommendations for improvement. The Committee, chaired by Justice Samuel Silverman, was composed of 15 judges and lawyers in the First Department.

The Silverman Committee issued its report in 1980. It concluded that section 660.24 was unduly cumbersome and should be repealed. Instead, the Committee recommended that the judge handling the case be trusted to select the fiduciary, but with certain limitations. Among the proposed limitations were that relatives of judges be ineligible for appointment and that former judges be ineligible for two years after leaving the bench. The Committee also recommended that fiduciary appointees be ineligible to receive more than one "substantial" appointment within a 12-month period.

The Silverman Committee's recommendations were converted to rule form and presented to the Administrative Board of the Courts. Following the opposition of the Judicial Conference and the Association of Supreme Court Justices, however, the Administrative Board rejected the rules and declined to refer them to the Court of Appeals.

Part 36 of the Rules of the Chief Judge

Several years later, in the wake of renewed public charges of favoritism in the appointment process, then-Chief Judge Lawrence Cooke proposed that fiduciaries be selected randomly from computer-generated lists of qualified candidates. Although this proposal was not adopted either, shortly thereafter a new set of rules was drafted, circulated for public comment and promulgated with the approval of the Court of Appeals. The new rules, Part 36 of the Rules of the Chief Judge, took effect on April 1, 1986.

The 1986 version of Part 36 governed appointments of guardians, guardians ad litem, conservators, committees for the incompetent, receivers and persons designated to perform services for a receiver.28 It was thought that these appointments were the most common and the most remunerative, and that it would be impractical to apply the new oversight procedures to additional categories of appointments. The new rules placed the determination of the appointees' qualifications squarely with the appointing judge.29 This meant that there were no minimum qualifications for placement on the newly-created lists of prospective appointees. And the rules provided that the judge need not even use the lists, so long as the judge set forth on the record the reasons for not doing so.

The 1986 version of Part 36 rendered ineligible for appointment any known relative of any judge of the Unified Court System, whether by blood or marriage.30 There were no exceptions, no matter how far removed the relative was down the judge's family tree or geographically from the appointing judge's court.

A key component of Part 36 was the limitation on the number of highly compensated appointments that an individual fiduciary could receive. The rules provided that no appointee could receive more than one appointment in any 12-month period for which the compensation was anticipated to be more than $5,000, except in unusual circumstances involving continuity of representation or familiarity with the case.31 No limits, however, were imposed on the number of below-$5,000 appointments an individual appointee could receive.

Finally, the rules imposed obligations on fiduciary appointees to make two separate filings. First, the prospective appointee had to file a certification of compliance verifying to the appointing judge that the appointment would not be in violation of Part 36 and specifying all appointments received within the previous 12 months.32 Second, after the appointment was made, the appointee had to file a notice of appointment with the Office of Court Administration.33 The notice of appointment was filed as a public record, and the Chief Administrator of the Courts was required to arrange for the periodic publication of the names of the persons appointed.34 The rationale underlying the filing requirements was to open up the appointment process to public view and to provide sufficient information to the appointing judge to facilitate compliance with the rules.

Changes in Part 36

The current Part 36 retains its essential character from its original enactment 15 years ago, with a few changes. In 1989, the rules were amended to disqualify a judicial hearing officer from receiving appointments in a court of a county in which he or she serves on a JHO panel.35 In 1990, the rules again were amended to require that the notice of appointment be filed "no later than the first business day of the week following the appointment," that the appointee certify in writing to the appointing judge that the notice of appointment has been filed and that no fees be awarded unless the appointee filed the notice of appointment and certification of compliance.36

In 1991, an 11-member committee was appointed by the Administrative Board to review the rules and recommend whether any changes were needed. The committee, chaired by Nassau County Surrogate C. Raymond Radigan, issued a report and recommendations in 1993. Along with a number of technical, fine-tuning recommendations,37 the committee recommended that the $5,000 rule -- that an individual appointee may receive only one appointment in a 12-month period for which it is anticipated that the compensation will exceed $5,000 -- be increased to $10,000. The Administrative Board and the Court of Appeals ultimately approved the technical changes, but rejected the recommendation to raise the $5,000 threshold.

Finally, in 1994, Part 36 was amended to include referees among the categories of appointments subject to the rules.38 And in 1996, the strict ban against appointment of any relative of a judge was loosened, to prohibit appointment of relatives of judges within the sixth degree of relationship (which extends to second cousins).

C. The Administration of Part 36

Individuals seeking inclusion on the fiduciary list must complete and send to OCA a four-page application with background information on education and experience, including all prior court appointments in the last five years, and the category (or categories) of fiduciary appointments requested. The information from the application is entered in a computer database, which can segregate the data by county, type of appointment and other criteria. The database is contained in the court system's Intranet computer network, which is available to judges and court personnel throughout the State.

OCA conducts no screening of the applications; except for relatives of judges within the sixth degree of relationship, all applicants are placed on the fiduciary list. Thus, any determination of a prospective appointee's qualifications is left entirely to the appointing judge, who has access to the database as well as the hard copies of the application forms.

Once the judge selects a fiduciary from the list (or not, if good reason is set forth in the record), the prospective appointee is notified and is required to file a notice of appointment form (UCS Form 830.1) and a certification of compliance form (UCS Form 830.3), which must list all appointments received within the previous 12 months. The certification of compliance form is filed with the court and placed in the court file. The notice of appointment form is filed with both the court and OCA.

The rules require that the notice of appointment form be filed within 10 days of the fiduciary's receipt of notification that the appointment was made. There is no mechanism, however, to enforce the 10-day filing requirement, and OCA will accept the forms no matter when they are filed. After the form is received, relevant data from the form is entered into the OCA fiduciary database.

When the fiduciary seeks approval to be paid and the compensation exceeds $500, he or she completes a statement of approval of compensation form (UCS Form 830) and submits it to the appointing judge for approval. The judge in turn signs the approval and submits the completed form to OCA.39 These forms specify the amount of compensation approved, and contain a certification by the fiduciary that the notice of appointment was filed with OCA (without which the judge may not approve any fees). Relevant data from the form is then entered in the database.

All of this information -- hard copies of the fiduciary applications, notices of appointment, statements of approval of compensation and information from these documents that is entered in the OCA database -- is available to the public upon request.

With the promulgation in the mid-1980s of Part 36 of the Rules of the Chief Judge, the court system began its first comprehensive effort to regulate the fiduciary appointment process in New York. Nevertheless, widespread concerns over the impartiality and fairness of the process have persisted. These concerns have been reflected in a continuous stream of newspaper articles highlighting questionable practices in the appointment process in a number of courts. Some of the articles revealed that former judges were receiving large numbers of appointments and in certain cases extremely lucrative appointments.40 Other articles documented the disproportionately large number of appointments received by high- level political party officials.41 Yet other articles focused on appointments received by close relatives of non-judicial court officials, and by persons who contributed to the appointing judges' judicial campaigns.42

The last concern was also the subject of a report of the Committee on Government Ethics of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York. That report examined the fiduciary appointments of two New York City Surrogates who had recently run for office. The report revealed that a majority of the Surrogates' appointments (66% and 54%, respectively) were received by lawyers who either had contributed to their judicial campaigns or worked with law firms that had contributed.43

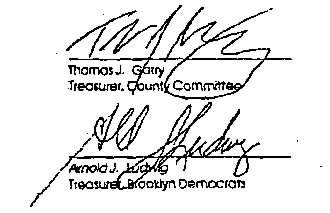

Concerns about political influence in the fiduciary appointment process were heightened by the controversial December 20, 1999 letter written by Thomas J. Garry and Arnold J. Ludwig. Thomas Garry and Arnold Ludwig, along with William Garry, comprise the Brooklyn law firm of Ludwig & Garry. Until recently, Ludwig & Garry was the law firm of choice for receivers in Brooklyn seeking to retain legal counsel (see pp. 29-30, infra). Arnold Ludwig, a former law secretary in Brooklyn Supreme Court, is an officer of the Brooklyn Democratic organization and was a member of the organization's Law Committee. Thomas Garry is also an officer of the Brooklyn Democratic organization and was a member of the Law Committee. Thomas Garry and William Garry are the sons of a sitting Brooklyn Supreme Court Justice.

Among their numerous appointments as counsel to receivers, the Garry & Ludwig firm was retained as counsel by the receiver originally appointed to manage the Cypress Hills Cemetery, which had been placed in receivership pursuant to an action charging mismanagement brought in Brooklyn Supreme Court in 1993 by the State Attorney General's Office. When the court replaced the original receiver in 1996, Garry & Ludwig was continued as counsel, and the firm was again continued as counsel when the court replaced the second receiver in 1998 with Manhattan attorney Ravi Batra. Although not himself a Brooklyn Democratic official, Mr. Batra employs the Brooklyn Democratic county leader in an "of counsel" capacity. The Cypress Hills receivership, which is still pending, has proved to be a particularly lucrative case for its fiduciary appointees, with over $1.5 million in fiduciary fees paid out to date.

In early December 1999, however, Mr. Batra wrote to Garry & Ludwig to advise that he was substituting his own law firm as counsel to the receiver in the Cypress Hills case and in three other pending cases in which he was serving as the receiver. Batra claimed that the Ludwig & Garry firm was incompetent and attempting to "churn" legal fees; Garry & Ludwig claimed that Batra was motivated by his desire to obtain legal fees in addition to his receiver's commissions. In any event, their removal from the cases motivated Thomas Garry and Arnold Ludwig to write to the Chair of the Brooklyn Democratic Law Committee resigning their positions as members of the Committee. They also sent copies of the letter to dozens of other Brooklyn elected and party officials. The letter was eventually obtained by the press, and the story was reported in newspapers throughout the metropolitan area in January 2000.44

In their letter, the lawyers articulated their understanding that their loyal service to the party entitled them -- not Mr. Batra -- to a continuing share of fiduciary appointments. They complained that their "diligent work and unquestioned loyalty to the Organization over the many years are clearly not as important as the desires of Mr. Ravi Batra [who] . . . . holds no party or elected position in our County" and "has never assisted the Law Committee on any level whether it be collecting signatures, binding petitions or trying an election law case, etc." The letter went on to state that "[o]ne cannot reasonably expect our firm to continue to avail to the Organization our professional services, the utilization of our employees, and the use of our facilities while the Organization sits idly by and permits Mr. Batra to maliciously injure our practice and reputation without consequence." The letter concluded with an expression of hope "that one day in the not so distant future we will be able to work together again when the interests of the Organization are once again paramount to the unfettered demands of one non-contributing individual." A copy of the letter is attached as Exhibit D.

C. Problems Identified by the Special Inspector General and the Auditors

The ongoing investigation by the Special Inspector General for Fiduciary Appointments and OCA's auditing staff has revealed serious flaws in the fiduciary appointment process. The investigation has confirmed many of the newspaper article charges, including those concerning the receipt of multiple and lucrative appointments by high-level political party officials, former judges and relatives of nonjudicial employees of the court system. Some of the major problems in the existing system are highlighted below.45

Political Party Officials have Received Numerous Appointments.

A number of high-level political party officials have received extensive appointments. For example:

- One county political party leader has received nearly 100 appointments.

- Another county political party leader has received over 75 appointments.

- The small law firm of another county political party leader has received

over 200 appointments.

- The small law firm of yet another county political party leader has

received over 100 appointments.

- A lawyer whose small law firm employs a county political party leader has received nearly 100 appointments.

Former Judges have Received Numerous Appointments.

Former judges have received numerous appointments, including some extremely lucrative individual appointments. The following are some examples:

- A former appellate judge has received nearly 250 fiduciary appointments.

- A former Surrogate has received nearly 70 appointments.

- Another former Surrogate has received nearly 60 appointments.

- A former Supreme Court Justice has received over 60 appointments.

- A former County Court Judge has received nearly 70 appointments.

- A former judge was awarded $424,000 in fees for a guardian ad litem

appointment obtained within three months of the judge's retirement

from the bench.

- A former judge was awarded $350,000 in fees for a receivership appointment

obtained within a year of the judge's retirement from the bench (the

fee was later reduced to $200,000 by the Appellate Division).

Relatives of Nonjudicial Employees have Received Numerous Appointments.

Immediate relatives of nonjudicial employees of the Unified Court System have received numerous appointments. For example:

- The spouse of a high-level managerial employee has received nearly

250 appointments.

- The spouse of a law secretary has received over 100 appointments

in that court.

- A county clerk's son has been retained as property manager in numerous receivership cases in that county.

Compliance with Filing Requirements has been Deficient.

The investigation has also revealed widespread noncompliance with the filing requirements of Parts 26 and 36 of the Rules of the Chief Judge. The following are examples from some of the counties investigated:

- Of the more than 400 Kings County Supreme Court receivership cases

reviewed, not a single approval of compensation statement was filed

with OCA, as required under Part 26. In addition, in those cases, only

22% of the receivers filed a notice of appointment with OCA and only

20% filed a certificate of compliance with the court, as is required

under Part 36. Of 50 Kings County guardianship cases reviewed, 76%

of the court evaluators filed a notice of appointment and 84% filed

a certificate of compliance, but only 25% of the guardians filed a

notice of appointment and only 42% filed a certificate of compliance.

Approval of compensation statements were filed for 76% of the court

evaluators and 53% of the guardians.

- In Queens County Supreme Court, 25 receivership cases and 25 guardianship

cases were reviewed, and in Queens County Surrogate's Court 25 cases

in which guardians ad litem were appointed were reviewed. In the receivership

cases, only 18% of the receivers filed a notice of appointment and

only 7% filed a certificate of compliance, and approval of compensation

statements were filed for none of the appointments. In the guardianship

cases, although 84% of the appointees filed a notice of appointment

and 77% filed a certificate of compliance, approval of compensation

statements were filed for only 52% of the appointments. In Surrogate's

Court, compliance was much better: appointees filed a notice of appointment

in 91% of the cases and a certificate of compliance in all of the cases,

and an approval of compensation statement was filed for 79% of the

appointees.

- In Nassau County Supreme Court, 25 receivership cases and 25 guardianship

cases were reviewed. In the receivership cases, only 23% of the receivers

filed a notice of appointment and only 15% filed a certificate of compliance,

and an approval of compensation statement was filed in only 15% of

the cases. In the guardianship cases, 84% of the court evaluators and

55% of the guardians filed a notice of appointment, and 89% of the

court evaluators and 64% of the guardians filed a certificate of compliance.

Approval of compensation statements were filed for 89% of the court

evaluators but for only 40% of the guardians.

- In Erie County Supreme Court, 24 receivership cases and 50 guardianship cases were reviewed. Only 23% of the receivers filed a notice of appointment and only 19% filed a certificate of compliance; approval of compensation statements were filed for only 30% of these appointees. In the guardianship cases, 41% of the court evaluators and 11% of the guardians filed a notice of appointment, and 24% of the court evaluators and 21% of the guardians filed a certificate of compliance; approval of compensation statements were filed for 39% of the court evaluators and 22% of the guardians. Fifty Surrogate's Court cases in which guardians ad litem were appointed were reviewed, and again the filing compliance was much better: 78% of the appointees filed a notice of appointment and 100% filed a certificate of compliance, and an approval of compensation statement was filed in 95% of the cases.

Problems also have been detected in the manner in which information from the filings is entered in the OCA fiduciary database. Names of appointees and amounts of compensation have been entered incorrectly, and multiple entries for the same individual are not uncommon (for example, John P. Doe could be listed as "John P. Doe," "John Doe," "J. Doe," "J.P. Doe," etc.)

The Rules were not Applied to Secondary Appointments.

As noted, the requirements of Part 36 expressly apply to "persons designated to perform services for a receiver." § 36.1(a). Nevertheless, a practice evolved in the courts in which the rules were not applied to secondary appointees such as counsel to the receiver and property managers. Thus, the receivers, and not the judges, selected their own counsel and property managers. Moreover, these secondary appointees rarely, if ever, complied with the filing requirements, and they did not consider themselves bound by any of the other provisions of Part 36, such as the prohibition against appointment of relatives and the $5,000 rule. One extreme result of this practice was that the three-attorney Brooklyn law firm of Ludwig & Garry, two of whose members are the sons of a sitting Brooklyn Supreme Court Justice, received 75% of all counsel to receiver assignments in Brooklyn Supreme Court from 1995 through 1999, generating hundreds of thousands of dollars in fees for the firm.

Fortunately, this problem has been addressed. In March 2000, Chief Administrative Judge Jonathan Lippman issued a memorandum to judges across the State emphasizing that the Part 36 rules apply to secondary appointments in receivership cases. As a result, it has now been made clear that judges must appoint the counsel and property managers, and that these secondary appointees must comply with the filing provisions and the other requirements of the rules.

Widespread Billing Irregularities have been Uncovered in Receivership and Guardianship Cases.

The investigation by the Special Inspector General and the auditors has uncovered disturbing trends in fiduciary billing practices in many cases. As discussed, receivers are paid a percentage of the amounts they collect and disburse; guardians usually are paid similarly, or they are paid based on a percentage of the assets of the incapacitated person (see pp. 8, 11, supra). In many receivership and guardianship cases, the receivers and guardians retain counsel (sometimes themselves or their own law firms), who are paid a separate fee, also from the assets and generally on an hourly basis. In some of the cases reviewed, the counsel performed strictly legal services, such as litigation. In many other instances, however, judges regularly approved legal fees for services performed by the attorney that were not of a legal nature and should have been deemed part of the receiver's or guardian's routine duties. The legal fees approved for these services ranged from $150 per hour to over $400 per hour; and, at least in the receivership cases, the fees often exceeded the receiver's commissions.

The following are some examples of the types of services for which hourly legal fees were routinely approved:

- Preparing the guardian's initial, annual and final accountings and

reports

- Preparing the receiver's accounting

- Locating heirs and obtaining family records

- Reviewing and reconciling bank statements

- Speaking with hospital and nursing home staff

- Preparing forms for filing with OCA

- Obtaining bonds

Courts Frequently Appointed the Court Evaluator as Guardian.

It is relatively common for the court to appoint the court evaluator (or, less frequently, the court-appointed attorney for the alleged incapacitated person) as the guardian. In fact, in eight of the 50 Article 81 cases audited in Brooklyn Supreme Court, the court evaluator was appointed guardian. Yet, because a primary responsibility of the court evaluator is to advise the court on whether a guardian should be appointed, this is a potential conflict of interest in some cases, raising an appearance of impropriety. An even more serious concern arises when the court appoints the attorney for the AIP as the guardian.

Limits on Lucrative Appointments may have been Widely Violated.

As discussed, except in narrow circumstances, Part 36 prohibits a single appointee from receiving more than one fiduciary appointment within a 12-month period in which the anticipated compensation will exceed $5,000. The investigation and audits have identified many individual appointees who received more than one appointment in a 12-month period for which they ultimately received compensation greater than $5,000. In most of these cases, however, it is extremely difficult to determine whether violations of the $5,000 rule occurred. This is because it is often not clear at the time of appointment what the total compensation, which is a function of a series of typically unpredictable factors such as the duration of the appointment, ultimately will be. For this reason, many have urged the Commission to recommend replacement of the $5,000 rule with a simpler, more enforceable limitation on appointments.

It is also apparent that, in many cases, fiduciaries avoid the restrictions of the $5,000 rule by deliberately reducing the amount of the compensation for which they seek court approval. For example, the investigation and audits have identified an exceptionally large number of fee applications in the $4,900 to $4,999 range. In fact, some fiduciaries have openly acknowledged in their fee applications that they were deliberately reducing their fee requests to avoid the strictures of the $5,000 rule.

Judges have Given Appointments to High-Level Participants in their Election Campaigns.

The investigation has revealed that a number of judges have given fiduciary appointments to high-level participants in their judicial election campaigns. Appointments were given to campaign managers, coordinators, treasurers and finance committee chairs. Some of these appointments were made within a year or two of the conclusion of the campaign.

D. Problems Identified by the Commission

The Commission's extensive study of New York's fiduciary appointment process has confirmed the existence of many of the problems noted above. The Commission has also identified other problems in the appointment process. Some of the additional problems are discussed below.

The Current Fiduciary Lists are Largely Unusable.

Under the existing rules, judges are expected to select fiduciaries from the lists of candidates that OCA compiles for each county of the State. In many jurisdictions, however, these lists contain thousands of names and are essentially unusable. For example, the New York County list has over 5,700 names, the Kings County list over 4,700, the Nassau County list over 3,900, the Westchester County list over 3,000 and the Erie County list over 1,700. The excessive size of these lists presents significant obstacles to judges seeking to use them in any sort of systematic way.46 Also, because the lists are not updated, they include many people who have retired, moved away or even died.

Inclusion on the Lists is Essentially Automatic.

The existing rules require no qualifications for inclusion on the fiduciary lists. There are no education or training requirements,47 and no background or experience criteria. In addition, other than relationship to a judge within the sixth degree, nothing disqualifies an individual from inclusion on the lists. Thus, convicted criminals, disbarred and suspended attorneys, bankrupts, individuals whom courts have removed as fiduciaries in prior cases for poor performance, and others who arguably should not be eligible for appointment now face no limitations on their names being included on the lists.

Certain Individuals Who Serve in a Fiduciary Capacity are not Covered by the Existing Rules.

A number of appointees who arguably serve in a fiduciary capacity and are paid from the assets of a party or the estate are not now subject to the existing rules. In some cases these appointments are made by the court; in other cases the individuals are retained by another fiduciary who has been appointed by the court. Those appointed by the court include: court examiners (who are appointed to review the reports and accountings filed by Article 81 guardians48); special needs trustees (who are appointed to establish trusts on behalf of incapacitated persons when funds remain after repayment of Medicaid liens); and private law guardians (who are appointed to protect the interests of children in matrimonial cases). Those retained by a fiduciary appointee include: counsel for Article 81 guardians (who are retained by guardians to handle legal, and often non-legal, matters); accountants for Article 81 guardians (who are retained by guardians to handle tax and other financial matters); and assistants to guardians ad litem (who are retained by guardians ad litem to perform investigative and other tasks).

None of these appointees are governed by the fiduciary rules. Thus, they do not file the required forms, and they are not subject to the limitations that apply to other fiduciaries, such as the prohibition on appointment of judges' relatives and the $5,000 rule.

Public Funds are not Available to Compensate Fiduciaries in Indigent Cases.

In a great many cases in which fiduciaries are appointed, particularly many Article 81 cases, the individual for whom the appointment is made has minimal or no assets. Unlike in other types of cases involving indigent litigants, such as criminal cases and most Family Court cases, institutional offices and private lawyers generally do not receive public funds to handle these assignments. Accordingly, the appointments become pro bono assignments, which can often impose unreasonable demands on those called upon to handle them. For example, at the public hearing that the Commission held in Buffalo, representatives of a legal services office testified at length about the tremendous time commitment and other pressures on their office that arise when the office is appointed without compensation as guardian in an Article 81 proceeding.49 The same concerns have been raised by private attorneys who have undertaken these pro bono assignments. This has led to a practice that some (though not all) have condemned -- the tendency of some judges to reward private attorneys who have taken pro bono fiduciary appointments with lucrative appointments when they become available.

Laypersons Believe They Have Nowhere to Go with Questions and Complaints.

At its public hearing in New York City, the Commission heard a litany of complaints from individuals who were parties, or had relatives or friends who were parties, in cases in which fiduciaries were appointed. The Commission also received numerous letters and written submissions from other complainants. Although the Commission had neither the resources nor the mandate to investigate these complaints, it is apparent that there is widespread mistrust and confusion among many people who are directly affected by fiduciary appointments. Much of this results from what the Commission has concluded is a widely-held perception that the court system and its representatives are not available to answer questions and investigate complaints that ordinary citizens have about the fiduciary process.

On the basis of its extensive examination of New York's fiduciary appointment process, the Commission has concluded that there are significant flaws in the current system. These flaws are present at every stage of the process: in the procedures by which individuals qualify for appointment; in the lists judges are expected to use in selecting appointees; in the provisions that seek to limit the number of lucrative appointments that individual appointees may receive; in the judicial scrutiny of applications for fiduciary compensation; and in compliance with the filings required of judges and appointees.

The Commission has identified a series of reforms, discussed below, that can vastly improve the current process.

A. Eligibility and Qualifications

Under the existing rules, anyone who applies (other than a relative of a judge within the sixth degree of relationship) can automatically have his or her name added to the OCA fiduciary list, thus becoming eligible for fiduciary appointments. In the Commission's view, it makes little sense to establish appointment lists, and expect judges to use them in selecting fiduciaries, if there are no criteria that render individuals eligible or ineligible for inclusion on the list. The Commission believes applicants should have to meet at least one critically important qualification -- fiduciary training -- to become eligible for the fiduciary list. At the same time, certain factors should render individuals ineligible for the list.

Training Should be Required for Inclusion on the Fiduciary Lists.

By statute, persons appointed in Article 81 cases as court evaluators, guardians or court examiners must complete a training program approved by the Chief Administrator of the Courts.50 These appointees need not, however, complete a training program to be included on the OCA fiduciary list. Other types of fiduciary appointees are subject to no training requirements at all, either to be eligible to receive appointments or for inclusion on the OCA list. A number of judges and bar association representatives have recommended to the Commission that mandatory training be extended to all categories of fiduciary appointees, and that training be required not only to receive an appointment but to be included on the OCA list as well.

The Commission agrees with these recommendations, and proposes that training programs approved by the Chief Administrator of the Courts be required for all those seeking inclusion on the OCA list. In particular, persons seeking inclusion on the lists for appointment as a "primary" fiduciary -- receivers, referees, Article 81 fiduciaries and guardians ad litem -- should be required to complete a training program on the substantive issues pertaining to that particular fiduciary category. For example, an individual applying for consideration as a receiver and also as a guardian ad litem should be required to complete a separate program for each of those fiduciary categories. In addition to the relevant substantive training, the programs should include instruction on the rules governing fiduciary appointments and the filings required of fiduciaries. Persons seeking inclusion on the lists for appointment as a "secondary" fiduciary51 should also be required to complete a training program, but their training could be limited to instruction on the rules and the filings. Continuing training of those who have completed the initial training and been included on the list should be required when necessary, such as when major changes in the law are enacted. In addition, all training programs should apply for Continuing Legal Education accreditation (see 22 NYCRR Part 1500), so that attorneys who complete fiduciary training receive CLE credit.

State and County Political Party Leaders Should be Ineligible for Appointment.

Among the fiduciary appointments in recent years that have generated the greatest criticism have been those received by political party leaders and their law firms (see Section III). Party leaders exercise considerable influence over the judicial nomination and selection process. The sheer number of appointments that they and their law firms have received thus raises a troubling perception that political considerations may be influencing these appointments.

Accordingly, the Commission recommends that State and county political party chairs, and their immediate relatives, be prohibited from receiving fiduciary appointments while they serve in that position and for a period of two years after they step down. Recognizing that this ban would not be effective if the partners or employees of political party chairs who are lawyers could still receive appointments, it is further recommended that the same prohibition apply to the partners, legal associates and other employees of the political party chairs' law firms.

The Commission also debated whether, as some have suggested, a prohibition on receiving appointments should apply to elected officials. Fiduciary appointment of elected officials raises many of the same concerns that arise from the appointment of political party leaders. For several reasons, however, the Commission decided not to recommend such a ban. It was generally agreed that prohibiting all elected officials from receiving appointments would be overinclusive; yet it would be extremely difficult to delineate which elected officials should be banned and which should not. Moreover, although elected officials have received fiduciary appointments, the investigation and audits have not revealed that they have received large numbers of appointments or particularly high-paying appointments. One explanation for this may be that, unlike political party leaders, who are not elected to their party positions (although they may be elected officials in other capacities), elected officials are subject to the ultimate check of the voters.

Immediate Relatives of Higher-Level Nonjudicial Employees Should be Ineligible for Appointment.

As discussed, under the existing rules relatives of judges within the sixth degree of relationship are ineligible for fiduciary appointments. No similar ban applies to relatives of nonjudicial employees of the court system, even though many of the same perceptions of favoritism can arise when their relatives receive court appointments, particularly when the employees are higher-level officials. As noted in Section III, immediate relatives of higher- level nonjudicial employees have received numerous appointments.

The Commission recommends that relatives of nonjudicial employees at or higher than grade 24 be prohibited from receiving fiduciary appointments.52 However, because judges, and not nonjudicial employees, actually make the appointments, this prohibition need not be as broad as the prohibition on appointment of relatives of judges -- prohibiting the appointment of immediate relatives (spouses, parents and children) of nonjudicial employees is sufficient.

Limitations Should be Imposed on Former Judges Receiving Appointments.

Fiduciary appointments of former judges have also generated concern and criticism. Some former judges have received an inordinate number of appointments, and others have received extremely lucrative appointments, in some instances shortly after they left the bench. The Commission recognizes that former judges often may be among the most qualified individuals to handle fiduciary assignments. At the same time, however, their appointment raises a serious perception that sitting judges may be rewarding their former colleagues.

In an attempt to strike the proper balance between these competing interests, the Commission recommends a prohibition on former judges (and their relatives within the sixth degree of relationship) receiving fiduciary appointments for a two-year period after leaving the bench. A two-year ban would be similar to other existing rules, such as the two-year ban on former State appellate judges practicing in their former courts53 and the two-year ban on former State government employees practicing or appearing before their former agencies.54 And it would enable the courts to continue to reap the benefits of the experience and skill of former judges, but only a reasonable period of time after they step down from the bench.

A two-year ban on appointments should also apply to former higher-level nonjudicial employees (as defined above) and their immediate relatives.

Disbarred and Suspended Attorneys Should be Ineligible for Appointment.

Clearly, attorneys who have been disbarred or suspended from the practice of law should not be eligible for fiduciary appointments during the period of their disbarment or suspension. The Appellate Division and the Office of Court Administration should arrange that OCA receive notice of disbarments and suspensions so that it may remove those attorneys from the fiduciary lists. Attorneys who are reinstated to the bar or whose suspensions have terminated should be eligible for appointments, but the disclosure required in the current application for inclusion on the OCA fiduciary list -- which calls for disclosure (with details) of any prior discipline by the grievance committee or the Appellate Division, including any pending disciplinary proceedings -- should be continued.55

Criminal Offenders Should be Ineligible for Appointment.

Persons convicted of a felony offense should be permanently ineligible to receive fiduciary appointments. The only exception should be if the convicted felon receives a certificate of relief from disabilities,56 and in that situation the individual should have to disclose the conviction in the application for inclusion on the OCA fiduciary list.

Persons convicted of a misdemeanor offense should be ineligible to receive fiduciary appointments for a five-year period following their sentencing. Again, the only exception should be if the offender receives a certificate of relief from disabilities, and he or she should still have to disclose the misdemeanor conviction in the fiduciary application. Moreover, in general, the criminal history disclosure required in the current fiduciary application -- convictions of all crimes and offenses, other than traffic violations -- should be continued.

Information Regarding a Fiduciary's Bankruptcy History Should Continue to be Available.

Persons who have been adjudicated bankrupt may not be the ideal candidates for fiduciary appointments, which often require the appointee to manage the finances of another individual or a business. Nevertheless, because federal law protects the rights of bankrupts to enjoy most of the privileges and benefits available to other citizens, it may not be lawful to render bankrupts ineligible for fiduciary appointments. Rather, so that judges and others have access to this relevant information, the disclosure of a fiduciary's bankruptcy history currently required in the fiduciary application should be continued.57

Procedures Should be Adopted to Remove Fiduciaries From the List for Good Cause.

No policy now exists regarding removal of an individual from the fiduciary list. Appointees who are derelict in their fiduciary duties, fail to file the required forms, engage in inappropriate billing practices or commit other misdeeds can be replaced as fiduciaries in individual cases. But there are no procedures in place to remove them from the list so that other judges do not unwittingly select them for future appointments.

The Commission recommends that the rules be amended to authorize the Chief Administrative Judge to remove an individual from the fiduciary list for good cause. The Chief Administrative Judge could act after receiving a complaint from a judge or litigant, upon a recommendation of the Special Inspector General for Fiduciary Appointments or based upon any other reliable information.

Some of the more difficult issues that the Commission examined involved the procedures governing the appointment of fiduciaries. These include matters concerning how a fiduciary should be selected, what role the fiduciary lists should play in this process and whether limitations should be imposed on the number and nature of the appointments that individual appointees may receive. The Commission's recommendations follow.

Judges Should Have Full Authority to Select the Fiduciary.

A seminal issue that the Commission addressed is the question of how a fiduciary should be selected. A few individuals and organizations, most notably the Association of the Bar of the City of New York, have recommended that a strict, or blind, rotational appointment system be adopted, with appointees randomly selected by computer from the OCA fiduciary list. Proponents of this approach point out that it would effectively eliminate any perception that favoritism or other inappropriate factors influence the appointment process. Although a strict rotational system is used to select bankruptcy trustees in U.S. Bankruptcy Court, the Commission is unaware of any state that has adopted this approach.

Others have suggested a variation on the strict rotational system. Under this approach the judge would select the fiduciary, but from a small list of names randomly generated from the OCA list. Yet another variation would be to allow the judge to depart from the randomly generated list, but a judge who did so would be required to provide a satisfactory reason. This is similar to the system now being used in Massachusetts.

The great majority of those who shared their views on this subject with the Commission strongly favor preserving the full authority of judges to select the fiduciary. They point out that potential candidates for a fiduciary appointment typically possess widely varying skills and expertise. They further note that cases in which fiduciaries are appointed can raise different issues and problems, and thus require particular services and talents. As a result, they argue, any system in which fiduciaries are randomly assigned will frequently fail to match the appropriate appointee to the appropriate case. Although judges themselves sometimes have difficulty making the correct match in some cases, they do a far better job than would a system of random selection.

There was considerable interest among Commission members in a rotational system for selection of fiduciaries. But after careful analysis of this difficult question the Commission has concluded that, assuming the recommendations set forth in this Report are implemented and prove to be effective in redressing existing problems in the fiduciary appointment process, judges should continue to have full authority to select the fiduciary. This is because, in selecting a fiduciary, the paramount objective must be to choose an individual who will provide quality service to the court, the parties and others affected by the litigation. That goal is best achieved when judges, in the exercise of their discretion, select a candidate with the skills and background needed to meet the task at hand.

The Commission recognizes that leaving the selection decision entirely to judicial discretion creates a risk of inappropriate factors influencing appointments. But that does not justify removing the selection authority from the judges, particularly where there are other steps, as outlined in this Report, that can be taken to minimize this risk.

Judges Should Select Fiduciaries From the OCA List.

The fiduciary rules should make clear that judges should select fiduciaries from the OCA list. Public perception of the fairness of the appointment process, moreover, would be enhanced if judges made every effort to appoint individuals with diverse backgrounds and experiences, including minorities, women and younger persons.

In certain situations, however, judges may have reason to appoint a fiduciary who is not included on the list. For example, an individual not on the list may have a particular expertise required in the case or may have some previous involvement with the case or the parties. In these and other limited situations, judges should have authority to appoint someone not on the list, but when they do so they should be required to provide a reason in writing. Appointees who are not on the list, however, should still have to demonstrate that they could qualify for inclusion on the list -- that is, that they meet all the criteria for such inclusion.58 Furthermore, they should be required to make the same filings as are required of those on the list.

Specialized Fiduciary Lists Should be Created.

If judges are to be expected to select fiduciaries from the OCA list, as we recommend, significant changes must be made in the current list. First, criteria must be established so that it is no longer essentially "automatic" for anyone to be added to the list. The eligibility/qualification requirements proposed above, including the mandatory training requirement, should go a long way toward making inclusion on the list a more meaningful status. Second, in many counties the current lists are simply too large. One relatively simple way to address this problem is to create specialized lists based on the fiduciary category for which the applicant is seeking appointment. Although some applicants request consideration for more than one category (or even for all categories), many do not. And if, as the Commission has recommended, training is required for inclusion on the list, a greater number of applicants will be more discriminating in the fiduciary categories for which they seek appointment. Specialized lists thus would be significantly smaller than a single, all- encompassing list and, as a result, far more usable.

Some have also suggested that the lists be categorized based on the experience of the applicants, similar to the programs that counties across the State have established to assign counsel to indigent criminal defendants. These "18-B" programs59 typically include a misdemeanor panel, a felony panel and a homicide panel, with ascending levels of experience required for each. Although this idea is worthy of further exploration, the Commission is not prepared at the present time to recommend that the fiduciary lists be categorized based on experience. In the Commission's view, it would be extremely difficult to develop fair criteria for determining which applicants should be assigned to which categories. In addition, establishing and maintaining these panels would require extensive effort and resources, akin to that involved in the assigned counsel panels.

Re-registration Should be Required for All Those on the Fiduciary List.

Another way to reduce the size of the fiduciary lists is to require periodic re- registration. The current list contains the names of hundreds, if not thousands, of individuals who have retired or are no longer available for fiduciary appointments. A re-registration requirement would provide a relatively simple means of removing these persons from the list.

The Commission recommends that re-registration be required every two years. The re-registration form should be a shorter version of the original application form, requiring that the applicant simply note any changes from the original application.

Additional Types of Appointees Should be Governed by the Fiduciary Rules.

The Commission has identified a number of additional court appointees who serve in a fiduciary capacity but are not currently subject to the regulation of the fiduciary rules. Court examiners, who are appointed by the court to review the reports and accountings filed by Article 81 guardians and are paid from the incapacitated person's assets, are selected from lists compiled by the Appellate Division and are not subject to the filing and other requirements of the fiduciary rules. The Commission has discerned no reason why court examiners should be treated any differently from other Article 81 appointees, and recommends that they be selected by the appointing authority from the OCA fiduciary list and governed by all other provisions of the fiduciary rules.60

Special needs trustees are usually appointed to establish and administer a trust (a special needs or "SNT" trust) so that a disabled person may continue to maintain Medicaid eligibility after receiving a substantial personal injury award. In carrying out their duties, they perform tasks similar to that of a guardian of property. These appointees, who receive their fees from the proceeds of the trust, should be subject to the fiduciary rules.

Judges in matrimonial cases make appointments that several bar associations and judges have maintained should be subject to regulation and disclosure. Guardians ad litem are appointed in matrimonial cases to investigate and report back to the court on particular issues, and their fees are paid by the parties. As such, they perform a function similar to that of guardians ad litem in Surrogate's Court cases. Although the current fiduciary rules could be read as applying to them, many courts have not viewed these appointees as subject to the rules. The Commission recommends that the rules make clear that they apply to these appointments.

In addition, in recent years "privately paid" law guardians are being appointed in increasing numbers to represent the interests of children in matrimonial cases. These appointees usually are selected from law guardian panels that the Appellate Division Departments designate pursuant to the Family Court Act.61 Although the distinctions between privately paid law guardians and guardians ad litem are not always clear (in both instances fees are paid by the parties), in general the guardian ad litem serves the interests of the court whereas the law guardian performs the more traditional role of a lawyer serving the interests of the child. Given that designation of law guardian panels is a statutory responsibility of the Appellate Division, the Commission does not recommend that privately paid law guardians be selected from the OCA fiduciary list. Nevertheless, it is recommended that these appointees be subject to the other requirements of the Part 36 rules, and that Part 26 be amended to make clear that judges must report the compensation they approve for privately paid law guardians.62

Additional Types of "Secondary" Appointees Should be Governed by the Rules.

As was recently emphasized, "secondary" appointees in receivership cases are subject to the fiduciary rules and must be appointed by the court, not by the "primary" fiduciary (see pp. 29-30, supra). The Commission recommends that other types of "secondary" appointees who currently are retained by court-appointed fiduciaries should also be treated as fiduciaries subject to all of the applicable rules. These assignments, which have become quite common and can involve substantial fees, include: counsel for Article 81 guardians, who are retained to handle legal matters on behalf of the incapacitated person; accountants for Article 81 guardians, who are retained to handle tax and other financial matters on behalf of the incapacitated person; and assistants to guardians ad litem, who are retained to perform investigative and other tasks. As is true in the receivership cases, the primary fiduciary should be able to request that the court appoint a particular individual for one of these assignments, but the rules must make clear that the actual appointment is to be made by the court.

New Limits Should be Imposed on the Number of Higher-Paying Appointments that Individual Fiduciaries may Receive.

Many have urged the Commission to devise a more workable limitation on the number of higher-paying appointments that individual fiduciaries may receive. Most view the existing $5,000 rule -- which requires a prospective fiduciary appointee to anticipate at the time of appointment whether his or her ultimate compensation will exceed that threshold -- as highly confusing and largely unenforceable. The Commission agrees that the $5,000 rule, at least by itself, is an ineffective means of preventing the concentration of higher-paying appointments in a few individuals.

Several alternatives have been suggested. Some have proposed that limits be imposed on the number of appointments that an individual may receive within a specified time period. For example, once an individual receives, say, five appointments in a 12-month period, he or she would be ineligible for an appointment for another year. In the Commission's view, such a rule would be unwise. It would do nothing to prevent the assignment of five highly lucrative cases to an individual appointee every year; and it would have the undesirable effect of preventing an individual appointee who had received five extremely low-paying cases from receiving any additional cases during the next year.

A more sensible approach is to limit future appointments based on the amount of compensation that an appointee has received over a given time period. Once an appointee has been awarded a threshold amount of compensation in all of his or her fiduciary assignments during any 12-month period -- the Commission recommends the threshold be $25,000 -- the appointee would be ineligible for another appointment for an additional 12- month period. For example, an individual who actually received $10,000 on March 1 for compensation in one case, $10,000 on April 1 for compensation in a second case and $5,000 on May 1 for compensation in a third case would not be eligible again for a fiduciary appointment until the following May 1. This would provide a clearer rule that would not require anyone to anticipate what the ultimate compensation might be in any case. And it would provide an effective means of preventing the type of deliberate under-billing -- that is, the spate of billings between $4,500 and $4,999 -- that has been used to evade the limitations of the existing $5,000 rule.